Friday, December 16

Lord of the Rings: Pacing

This pulse allows us to feel and think in the space of a breath before the conflict turns in another direction. Remember that all of the relationships in the Fellowship resolve in this sequence: Frodo's suspicion reaches a new anxious pitch, Frodo's acceptance of his destiny reaches new depths, Boromir redeems himself, Aragorn accepts that Frodo most continue alone, Pippin and Merry remain with Aragorn, and Sam shows he'd rather die than leave Frodo's side. And that's the end. We know where all the characters stand. We know Frodo's direction - his fears, his quest, his desire, and his lingering reluctance. The director and screenwriters created an ending that isn't an ending, a cliffhanger that doesn't leave us feeling cheated. The pulse in the pacing is genius.

I'll be looking for more of the same in Jackson's Big Hairy Movie.

Wednesday, December 14

Ho, ho, ho! Let's see what's in the sidebar for good boys and girls...

Strivers

Neal: This guy does everything, and most important, sells cool merch. See not-the-Buddha. Me, too.

Fresh Hell: She lives on the frontier where game/film/TV creation is converging. In the next two weeks, this introvert is going to post something that you thought. But wouldn't admit. Or say as well.

Awful Writer: Because he had the good sense to pull together advice into the Hall of Fame and moved in with his MIL (Mother in Law) in the Hollywood Hills, which requires first great sense, then karma, and cojones. It was great to meet you, dude.

More pros and industry entertainment

The Artful Writer. Speaks for it(them)self.

Kung Fu Monkey. What can be said about Kung Fu that could possibly add anything to the Monkey?

Happy Fun Goodies!

These folks so thoroughly linked to that I'm going to spare them the insignificant traffic that might reach them from Darkness Visible. Still, I read them. Blog candy. I can quit anytime.

I find your lack of faith disturbing. Don't we all.

Query Letters I Love. Lesson: Never query the Empress.

Assistant/Atlas. Nothing succeeds like success.

If you got a lump of coal in this blogroll, send me a note. I know I met more of you than I've added here, but some of you didn't look at all like your home page.

Friday, December 9

Aeon Flux

Flux is a great looking movie that left me unmoved, much the same way Serenity did earlier this year. Nevertheless, I think it's a pretty damned successful example of the genre. But two sci-fi features a year exceeds my quota. (Technically, The Revenge of the Sith falls into this category, but it was an opera without music, not a movie.) The emotional claim such movies make on the audience is slight. Moviegoers, especially fans, are fine with that. But I'm not.

Flux attracted me because I'm a huge fan of a great action movies. Also, Charlize Theron attracts me. (D'uh.) While action in action movies is a battle between foes, sci-fi action is a battle between moral forces, often thematic conceptions at that. Characters, even when played by strong actors like Theron, are two dimensional. The production design and locations heighten the black and white of Aeon's view of the world as a freedom fighter amped up by rage at the murder of her friend. But when the moral themes are the flywheel of the story, you want them to turn all the gears up to a screaming RPM.

The engine sputtered out in the third act, as it did for similar reasons in War of the Worlds. The twist had the same effect as the old trick of characters waking from a dream. All the desperate fighting that leads up to the breech in the city wall is moot. Nature was winning the battle while the experiment in the human petri dish called Bregna was collapsing. (In WoTW, the festering ooziness of organisms is killing the robots.) While I agree with the idea that evolution and the profusion of organisms are "smarter" than engineers or sentient robots, all that pursuit and battle leads to this revelation? You can argue that it's human nature to make such a mistake, but good dramatic structure? Not so much. Theme overtakes the story, making deus ex machina admissible. For shame.

And that is why I'm not a fan of this genre, or maybe, these three movies. The great human urge of protagonists in movies, especially in a the U.S., is that you and I could be the hero. We may just be entertaining ourselves, not philosophical speculation. But if you make a movie that leads us to believe in a man or woman's power to change the course of history, do not pull the plug in the third act. Shame! Do no raise my hopes for the likes of Tom Cruise - shame! - and the lovers in Aeon Flux, and them show me that the human race would have been saved anyway. Shame! Shame! Shame!

Monday, December 5

The Idea: Step 1 of The Discipline

Take any screenplay you're struggling with and I'm willing to bet that there is a problem at the heart of the idea. Here's what makes me think so. Frame a movie - any movie - the way Chris did (some examples his, some mine):

- A determined police officer reunites with his wife on Christmas eve.

- A man who fears he's lost a sense of magic in his life pursues possible extra-terrestrials.

- A police chief reluctantly takes on the hunt for a terrorizing shark.

- A poor boy wins a once-in-a-lifetime chance to meet his chocolate-making hero, and weird confectioner chooses the heir to his candy-making empire.

- A writer pursues a murder story that makes, and ends, his career.

- A smokejumper revenge for his murdered father.

The initial reaction to an idea is, "Huh! That has potential." The idea isn't the theme, the logline, the plot, or the pitch. It's characters and action that imply at least one very intersting story.

Since Warren has posted about his first screenplay, let me jump on. My first screenplay - the smokejumping revenge drama - was not so much writing as archaeology. I rewrote it until I'd dug up the idea. It took a lot of digging. I taught myself a great deal along the way. No complaints. But that's the the hard way. The two-year long way. (Probably the I'm-not-done-digging way.)

The test of a movie idea is: When pared down to that simple idea sentence, is it an interesting, sustainable visual story? Who wants to spend a year rewriting the first impossible 60 pages of a notion because a few imagined scenes seemed irresistible? I've already shelved one, well, "thing" that I thought was an idea, but to date, it isn't. The Idea Test acts as a scale: if it's not a movie, is it lighter (tv), heavier (novel), compressed (short story), or broad (a sketch)?

Key: Die Hard, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Jaws, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, Capote, the first John-the-Edutainer screenplay.

Sunday, December 4

Help save the Brattle Theater programming. They paved paradise...

The underappreciated Brattle Theater in Cambridge MA is facing the overthrow of its independent programming because operating/real estate costs increased while audience numbers held or declined. If you've seen a great old American and rare foreign movie on the big screen, you've probably seen it at a theater like this one.

Here's what I'll do. I'm going to give a two-dollar contribution (is that queer?) for every contribution made at the Darkness Visible Brattle Theater Fundraising page. So, if you have a sense of gamespersonship, you'll contribute often. If you contribute a one-time amount of fifty dollars or above, I'll do the right thing and up my percentage.

Do it as a holiday gift, do it in honor of a friend who loves movies, do it because you remember the first time you cried in a theater. Obviously, don't feel obliged, but we're all in this together, right?

Monday, November 28

The Dali Lama Effect

It's real, of course. "Be present in the moment." Simple yet profound. But forgettable, especially when I say it. But you drive 45 minutes to see the Dali Lama, and he chuckles about his car ride through (your city here) and he says, "Be present." It will resonate for days. You will notice, at least, that you're not present. Not in the moment. Suddenly the obvious is true of you. This is the Dali Lama Effect (DLE) in action.

Welcome to the Screenwriting Expo, where everything you taught yourself in the hothouse of your local coffee shop rises to the lips of some very good teachers, and seems truer, deeper, wiser. And you know what? It is. Because you wanted it. You really wanted it. I'm leery of the DLE but, O ye empty heavens, I'm grateful! I'll be sharing some of the things I relearned in coming posts.

The Darkness darkness follows a week of vacation and week of visiting family. Visiting home (or the home of the The One You Love) always raises the question: is there a story here? Naaah! Besides, one way or another, you're already writing that story.

Also, for those dogged few of you who followed a link to my journal site (Busman's Tour), forget it. It's all happening here. Now. Be present.

[Photo: Q: Just what kind of convention hotel did you stay in? A: The kind with "plus service" such as this.]

Thursday, November 10

Shopgirl

If she were your friend, you'd tell Mirabelle Buttersfield she needed to quit hoping that Ray Parker will come around. After a few too many beers, you'd slap her and scream, "Wake up, wake up, wake up!" Because whatever half-lived dream she's stuck in, it's excruciating to watch. The movie of her story is deliberate, affecting, and slight - dated and pre-feminist in ways that may be telling us that men and women are all taking leaps backward.

She's vivid, sure, but Mirabelle lingers in the voyeuristic, fetishistic fascination of the writer (Steve Martin) and director (Anand Tucker). For her, or them, the last forty years in

I can't decide which gave me the more acute case of the creeps in this movie. Whether it was the nearly unaccountable liveliness of Mirabelle, contrasted with the emptiness of

Tuesday, November 8

Out of the Darkness

It's official. We'll gather at the Veranda bar at the Figueroa Hotel on Sunday night, November 13th and dare to look at each other's god-given faces in three dimensions. Illustrations and other particulars can be found at Warren and Joel's sites.

The idea for a live, in-person meeting of screenwriters from the blogosphere to coincide with the Screenwriting Expo started at Dave's site, and quickly took flight thanks to L.A. local men Warren and Fun Joel.

Warren promises to buy drinks if he wins the Creative Screenwriting Open scene competition. The gauntlet is down. Single-malts at dusk!

Wednesday, November 2

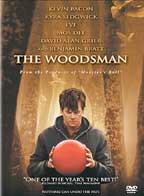

A fan letter to Nicole Kassell

The Woodsman, your first movie (written and directed), knocked me out. I can'’t think of any observation worth mentioning that can take away from the total effect.

When people say that all the really terrific, boundary-crossing stories were told in the '70s, I say: "“Three words: 'bullshit,' and '‘The Woodsman.'"” Here are just some of the ways you made a great movie.

Generally: Simple. Direct. Unflinching. Unsentimental.

Specifically, visual imagination: When Walter (Kevin Bacon) and Vicki (Kyra Sedgwick) first have sex, the editing takes us into the moment, but it is a moment interposed with after and before. This scene shows us the weight of anticipation and afterthought, of anxiety and shame that Walter feels.

Story moment: Hanging in the air in a story about pedophilia is the question, "“Is Walter still a compulsive lover of little girls?" And until the audience gets an answer, they keep him at arms length. If he is, he may deserve the viewers'’ disgust. By establishing a sexual and, by slow degrees, intimate relationship with Vicki, the audience begins to trust Walter. There are signs he'’s changing. We hope he achieves his "“normal" as much as he does.

Music: The absence of music at a number of points intensifies the dead-on stare this story uses to examine Walter'’s transition and struggle to become a good man. Immediately before Vicki and Walter play pool to "There's a whole lot of rhythm going round...,"” a silence hangs in the air like real life. That long. That uncomfortable.

Acting: Less than a half hour into the movie, Vicki learns Walter'’s secret. She sits in the truck and it washes over her. She sits still. She doesn'’t erupt with emotion. Tears, vomiting, rage. These were all possibilities. But by containing her emotion, the audience learns that Vicki is much stronger than we realized. This scene sets the stage for her to reveal that she has been sexually abused too, but that she doesn'’t hate her abusers.

As you can see, most of these observations come from the first half of the movie. By the 45-minute mark, all of the strengths of the movie are in play and the story follows its course naturally. Thanks for such good work, and for your careful choice of material to adapt.

Looking forward to your next movie,

John

Sunday, October 23

Creating Sympathy for Eric Brockovitch

But when the audience thinks that everything could turn against her - her man, her kids, the plaintiffs, even her boss - a brief important scene restores hope to the audience and Erin. She has awakened on a seedy motel couch. George wakes up the kids and takes them out to breakfast, resigned now and sullen, but committed to helping. Erin's son Matthew sits at the desk reading information about one of the plaintiffs. "This girl's my age," he says. Erin bats it away, telling him not to mess up her files. He offers to bring breakfast back from the restaurant. She accepts.

Matthew recognizes what she's been doing: helping kids like him who are sick and dying. With his exit, she knows that her family will be there after the case no matter what. But she also knows that the stories in the case have the power to change minds, that they invite listeners to identify with the victims. Her hope is restored as well. The audience learns that her crusade has not become an obsessive idee fixe. She is still motivated by compassion and outrage at injustice.

Tuesday, September 27

Darkness goes dark to allow for the filling of certain bank accounts

And in the meantime, don't miss The Woodsman: simple, unrelenting, unflinching, and a complete success.

Friday, September 16

Central Station

They're over-confident. This is such a worthy story with too much slack in the middle. The second act - all of it on the road - shows little of Dora's (Fernanda Montenegro) real motivation. In fact, the conflict between her actions and words defuse her character's strengths. She is a clever, conscience-free pensioner eking out a living writing letters for illiterates at a dollar apiece. She doesn't mail them. In other words, no one cares. After reluctantly taking a stray boy whose mother is run down by a bus, Dora tries to return Josue (Marilia Pera) to his useless father. But she believes that children should never return to bad fathers. She is one of those children. Dora tries to impose the lessons of her past on Josue, first by not sending the letter Dora penned for his mother - cruel but trivial - and selling him for adoption - callous and self-interested. She finds a little humanity through a friend's conscience. Dora rescues the boy when she's convinced that the brokers sell the kids for organ donation. But she keeps the payment.

When Dora flees with Josue, she never becomes desperate. She lies and steals, gets drunk, goes broke. She sweats, but then everyone sweats on a Brazilian bus. In the many prolonged scenes, the filmmakers try to show us who Dora and Josue really are against the blue and golden back country of Brazil (not what I saw on my visit). To sustain the duration, I wanted to see inner motivation revealed (okay, she talks about it, but that's not film, that's theater) or their desperation heightening. The second act flags as Dora's original motivation goes soft (to get rid of the boy), and no new motivation clearly emerges.

In the third act, Dora learns that Josue's father intended to find the boy's mother in Rio. And in a moment, she turns from her lifelong anger and prejudice against her father. Did he really love her, but simply couldn't find a way to tell her? Dora leaves the boy with his two grown brothers, allowing him to hope that the man will return.

Central Station is a good example of a bad idea: saving the drama of the main characters' inner conflict until the third act. It shows us her epiphany, but not the change. She was ruthless and venal, and now she's broke and admits that her heart has always been broken. A genuine insight about being alive, but not a change, not an arc.

Hiatus/Return

A note about liking movies but getting all up in their Koolade anyway: I like many movies I see. When I noodle about what makes them less than riveting, appealing, or piercing, I end up saying what's wrong. And I feel guilty. I don't enjoy doing it. Mind you, I'm only talking about the story is see. I liked stuff in the Spielberg mess The Terminal. I liked Central Station: a beautiful movie with a story full of often unrealized potential. And I really enjoyed Junebug, but I didn't think it hung together very well.

I'm not offering these observations lightly. Even industry executives said in a recent NY Times (story link is archived at the Times, but you can find it here) story that box office was down because "the product is not quality." Or "We make crap." Sure you do. Because it's hard to make interesting movies that must make money and appeal to a wide audience. Laundry detergent. That's what makes money and appeals to a wide audience. Still, I feel guilty.

So, I'm going to go on sounding like I think there's something wrong with everything I see. Darkness Visible didn't review The Terminal, right? Cause it's not worth the time. But here's why it's interesting: put your protagonist in a building he can't get out of. Even a big building. Create some drama. I dare you. Sure, watch Jeff Nathanson and Steven Spielberg fail. You and me, we'd fail, too.

Wednesday, August 24

Junebug

Somewhere, David Mamet sagely said, "Film is uninflected juxtaposition." Junebug relies on this aesthetic. There is rich potential for telling contrast among the cosmopolitan Madeleine (Embeth Davitz), her new husband George's (Alessandro Nivola) family, and the primitivist "outsider" artist (Frank Hoyt Taylor) whom she goes to North Carolina to wrangle into her gallery's stable.

Though the movie shapes up as an ensemble piece, this is Madeleine's story. She makes what appears to be critical choice in act two: family or ambition. Madeleine chooses to spend the evening winning the artist David Wark rather than sit by Ashley (the extraordinary Amy Adams) as she loses her first baby at term.

Leading up to the moment Madeleine chooses, she has seen her husband reveal a past she neither knows nor understands (singing an affecting hymn at the church dinner), her brother-in-law as a desperate and angry boy (making a misguided pass at her), her sister-in-law desperate and determined to soldier on through a passionless marriage (idolizing, crushing on Madeleine). None of these developments influence her relationships. Nor do we see them juxtaposed with her ambition. If anything, her ambition is moderate, balanced. Making Wark a client will not make her career, or kick her into the top tier of galleries. Wark himself - oracular, borderline schizophrenic - might have brought her a message from the angels. But she does not hear a mythic truth that stabs her with transformation.

What can we hope for Madeleine, fear for her? She's almost impenetrable. She breaks down at having made the wrong choice. "Why?" isn't clear. Almost to a person, the actors' performances are outstanding, and still there's no wind in the second act.

Uninflected juxtaposition demands design. See any David Mamet movie. You get a little pinch in each scene. Like the painter whose mission is guided by voices and appearances that he paints, director Phil Morrison and writer Angus MacLachlan have sketched something that may happen and left us wonder what that might be.

Wednesday, August 10

March of the Penguins

This beautiful movie about the Emperor penguins’ annual mating migration across 70 Antarctic miles is a triumph of cold-weather filmmaking remarkably free of the story techniques that motivate many wildlife documentaries. Whether you enjoy the light touch of March of the Penguins will depend on whether you trust the filmmaker.

What makes the movie so vivid are the many things it’s not. Not simply survival story, fight against possible extinction, Chaplin-esque slapstick, sentimental birthing account, and not an educational tract about why penguins do what they do. The structure is as simple as any journey story: they are compelled to leave the comfort of “home,” they go and strive and struggle and mostly survive extreme obstacles, they are transformed (into parents), and they return home. Penguins is as penguins does.

The cinematography is beautiful, the Emperor couples charming, their chicks undeniably endearing the music often cloying, and the narration intrusive without being informative. The penguins' soulful postures suggest how we should feel. But we learn so little about their obstacles and their biology that it is difficult to identify with their plight. So the movie becomes a green-screen against which viewers project themselves, and the drama of their longings and fears. For the birds, this is a journey from place to place for a purpose, not a love story as narrator Morgan Freeman intones. This is what I do not trust. I’m being pandered to.

Friday, August 5

Hustle and Flow

Writer and director Craig Brewer lets DJay (Terrence Dashon Howard) off easy and often. It's why we like DJay. And it's why we think he's sure to fail. Though the first rap song he pens is Beat that Bitch - or softened for ready airplay, Whoop dat Ho - when one of his girls verbally emasculates him and threatens to take whip hand in the household, he throws her out without a whoopin'. DJay gathers around him, thanks largely to coincidence, a handful of talented wannabes and Big Opportunities. Skinny Black, a hometown boy made bad in the rap world, is coming to town. They overcome obstacles to cut a cassette (?) dub of a couple original songs, including You Know It's Hard Out Here for Pimp. Bad wages, poor working conditions, and adversarial labor relations. All that makes pimping hard, but what's at stake if DJay fails? When the power meeting with Skinny goes south, and DJay goes to prison, it is of course, his peeps who bring their collective dream alive.

What's great about the story is the way DJay becomes the designated hope-ster. Nola (Taryn Manning) wants some vague other thing in a future that's better than tricking under the train bridge. Key/Clyde (Anthony Anderson) wants to do original work that has feeling. Contrast this with recording court testimony. Shelby, on percussion and keyboard (DJ Qualls), wants to do other than service vending machines. Nola says it sounds worse than her job. And Shug (Taraji P. Henson), his longtime, wide-eyed, pregnant whore, wants simply to believe in something good for the baby she's about to give birth to. And they all pile on for the ride.

As a parable about believing, and achieving, a dream, Hustle and Flow preaches that it takes a lot of people to give a dream a pulse. If it's a parable about movie-making, then the movie is a shout-out saying that sacrifices must be made, flesh peddled, dreams retailed, drugs purveyed, and in the end fine-tuned talk transforms a thought into an entertainment. And that it's worth it.

Sunday, July 31

War of the Worlds (WoTWo)

From the moment we see a 302" V8 in Ray Ferrier's kitchen, to the appearance of the first invading alien tripod, to another alien's last onscreen breath, director Steven Spielberg, the movie maker, is as good or better than ever. But even under the blockbuster rubric, which forgives many sins especially those of improbability, the movie is thematically hollow. The rush is real, but the memory fades.

The rush keeps coming. When Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise) and his children get into the open, Spielberg reminds us of the pervasiveness of the alien threat. Having escaped from a murderous mob and the tripods at least twice, Ray and his family wait to let a train pass at a crossing. The audience feels such relief at their escape, so reassured that the train is running, that when it speeds through burning from every window, the shock takes viewers' breath away.

There's a sweet transformation too in the way the axe becomes a weapon in the hands of Ray and Harlan Ogilvy (Tim Robbins). Harlan brandishes the axe, threatening to attack a tripod's steel tentacle. Ray persuades him not to. Audience members laughed when that axe appeared. It's that outrageous an idea. But when the tentacle grabs Rachel Ferrier (Dakota Fanning) and Ray attacks and severs it, the act was so well justified by Ray's absolute protectiveness, that viewers believed he succeeded, was smart to do it. That's the difference between character motivation (Ray) and a loony character (Harlan).

The dark view of humanity in this movie, and in HG Wells' book (according to reports), make the ending a sentimental box office ploy. Think back over the scenes of human conflict and see what selfish animals we are: marriages break, children steal cars from fathers, reporters pick among air crash victims for food, people steal cars from friends, one man murders another (for a minivan). The only generous character is Harlan, whose nominal mental stability disappears quickly, and whom Ray feels compelled to murder so that he and Rachel can survive to flee. Look back at the first tripod appearance: the first building destroyed is a home, the second a church. This broken-family reunion is no more than a quick patch and paint job.

Unfamiliar with the way Wells ends his story, I was shocked to find that the human spirit endures and thrives because we are lucky by evolution to have an autoimmune system. The first time people bring down a tripod, it is misleading. Ray stuffs a belt of grenades up the tripod's pie-hole, and thar she blows. Turns out, the real danger was giving Tom Cruise a big wet kiss.

Sunday, July 24

Wedding Crashers

If you laughed, Vince Vaughn, Owen Wilson, and director David Dobkin made it to first base. Second base if it made you horny. “Love triumphs after all” came to mind -- third base. If you thought this was a great movie, you got screwed and liked it. But I must have liked the piece I got (so a longish post).

Funny, sexy, sometimes very clever, the movie’s worth the ticket price. But don’t buy popcorn. Wedding Crashers’ clever premise builds a showcase for its stars and their onscreen lovers, who spend the second half of the movie sweating under the weight of set pieces they’re carrying.

In the first nearly perfect seven minutes, we meet John Beckwith (Owen Wilson) and Jeremy Klein (Vince Vaughn) and learn things that pervasive advertising hasn’t dropped trou about. The pair are divorce mediators who mount a charm offensive on divorcing combatants. The scene goal: to compromise on who gets the frequent flier miles in the divorce. John and Jeremy evoke sentimental memories of the wedding and invoke the promise of getting laid afresh tomorrow. The couple’s resolve softens. The scene perfectly shows – not tells – John and Jeremy’s M.O.: using the power of weddings to soften hearts, faith in their indomitable charm, and the imperative of sex. The wedding crashers’ C.V. Bullseye.

The second stunning sequence is the wedding season. The story compresses the entire season of maybe twelve nuptials of varied religions and classes into about eight minutes. John and Jeremy follow the rules of their hero, Chaz Reingold (Will Ferrell), legend and Yoda of wedding crashers: have a good back story, know the family, win the kids, charm the old ladies, avoid the cash bar (or wear a borrowed purple heart and leave your wallet at home), slap backs, joke, poke, go.

This orgy of ingratiation, dance fever, and taffeta-on-hotel-room-floors ends in ejaculations of champagne bottles. Oh, why can’t R-rated comedy always be this clever and naughty? But John, about to conquer another beautiful woman’s country, stalls in self doubt: he’d actually like to know who he’s shagging.

Exhausted and empty, completely unlike the tumid Washington monument in the scene, John is relieved the season is over. But Jeremy throws down the gauntlet: Treasury Secretary William Cleary’s (Christopher Walken) oldest daughter is marrying and crab cakes will be outstanding. Rule number (pick a number): never crash a wedding alone. John relents to pose as Jeremy’s brother, a partner in venture capital firm for socially responsible entrepreneurs.

John wants to more than bedding beautiful bridesmaids, something he soon recognizes as love. Jeremy wants to win, place, and show in what he calls the “Kentucky Derby” of weddings. While John is transforming into the best damn guy in the world, except of course for lying about his identity and propinquity to Cleary blood, Jeremy wets his wick with Gloria Cleary, who claims it was her first time. She pulls back her eager, bubbly mask to reveal a “stage-five clinger.” Meanwhile, John falls for Claire Cleary. From this point on, some funny stuff happens, but it has little to do with the what these characters want: love (John), and to get the hell out of there (Jeremy).

At this point, the movie turns episodic, giving us more time, presumably, to really, really like John (Wilson). Jeremy fights numerous foes (Gloria, fulfilling his bondage fantasies - but given Jeremy’s taste for adventure, how much is he suffering anyway?; Todd, the creepy gay brother who develops a crush on Jeremy (homophobia cliché); and Sack Lodge, Claire’s boyfriend, who’s vents his entitled rage on Jeremy). But his real conflict is with John, who won’t let Jeremy leave until Claire knows he loves her.

The movie repeatedly missed opportunities for hilarious conflict between Jeremy and John. Imagine Jeremy being subjected to these indignities as suffering for his loyalty to John. It would have upped the stakes, and each scene would turn into a test of their friendship, a test of what each of them will do for love. And what people will do for love, well, that’s funny.

Me? Second base.

Wednesday, July 20

Fallaciousness Duly Noted

So, refining the purpose, I submit that Darkness Visible asks, “What makes a movie an effective, affecting story? And what would have made it better?” If I were going to write it better.

A little fallacio (sp?) and a much good intention. I stand corrected. Thanks, dude. And, I've refined the subhead.

Monday, July 18

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

"Who can take a rainbow," and steal it from the shining edible world of Willy Wonka? Johnny Depp and Tim Burton can. While a lot of sweet and salty tidbits emerge whole from Roald Dahl's book in this new version of the movie (or remake, if you like. They're that similar.), Willy Wonka is creepy. Not that it would matter, if Depp's boy-man characterization helped move the story forward.

Digression: Why is this movie being so well reviewed? It's a visual feast -- a faithful, inventive, by turns edgy and gross-out realization of Dahl's original candy recipe. Love the story: see the movie, with a wildly more conflicted Wonka, and a much richer character in Charlie. And this version comes at a time when parents are child-obsessed. It's a delight to watch spoiled children and their parents suffer the consequences of their choices.

Not much moves this, or the original, story forward. This is why filmmakers may like it so much. There is so much to see and so few story threads to manage. First, children vie to find five golden prize tickets. Then they follow Wonka's whims on a magical mystery factory tour. The two film Wonka's try to add interest using different strategies, though the older is better.

In the Mel Stuart/Roald Dahl/Gene Wilder version (1971), Wonka cleverly stages a test. Charlie and Grandpa Joe break the factory rules, but Charlie redeems himself by giving up a top-secret candy sample that rival Slugworth would have paid obscenely to reverse engineer. Charlie wins by an act of integrity, even after getting carried away by a little harmless temptation.

In the Tim Burton/Johnny Depp production, Charlie and Grandpa Joe don't break the rules, but Charlie wins by default. Now, by the time Charlie is the last kid standing, we have a lot to like: his generosity, family feeling, lack of shame about eating candy. But he wins because he's not spoiled. He wins by doing nothing, a story shortcoming that must be laid Dahl's feet.

What's new and great: Charlie's poverty is greater this time. So great in fact that we pity him when his father (a character restored to the story) brings home from work a misshapen toothpaste cap and Charlie calls it the perfect gift. But he pulls a model of the Wonka factory from the cupboard - all toothpaste caps - and gives the Wonka figure the top hat he deserves. The image of the model and the revelation perfectly communicates the Buckets' poverty and Charlie's fascination.

During first act exposition, we learn the wonder, and then closing, of the Wonka factory through Grandpa Joe's eyes. Screenwriter John August wrote him as a former employee put out of his job when espionage forced Wonka to hermtically seal the place. And this change gives new weight and interest to Grandpa Joe's desire to return to the factory with Charlie.

Too much has been said elsewhere to comment on how hard it is to find something sympathetic in this entertaining new Willy Wonka. Watching Charlie preside over dinner with all the Buckets and Wonka in the final scene, you can't help but think, "Thank god someone with sense is taking over Neverland."

Friday, July 15

My Summer of Love

I confess. A well-reviewed movie about two teenage girls who fall in love, try on clothes, and then tempt a religious convert sounded like a titillating couple of hours. And though langorous and direct in its sensuality (not disappointing in the teen lesbian department), the film feels like a batch of episodes without much disicipline in the story department.

As the episodes follow one another, the story simply unspools. Actions don’t have consequences: Mona (Natalie Press), in an act of loyalty, throws a garden nome through the window of a particular Jaguar, Tamsin’s (Emily Blunt) father’s car parked in his mistress’s driveway. Tamsin is haunted by her sister Sadie, who died of anorexia. But in the third act, Sadie appears, fit and filled out the way a young woman might wish to be. It’s played for reaction, which a cheap use of both Sadie and the betrayal.

The effect: characters are aimless ciphers. And that’s a different thing entirely than human beings who are powerless to affect the other’s lives. The first is a storytelling failure. The second is a philosophical assertion. The emptiness at the heart of the story comes from the directors’ goal of telling a story by metaphor and rather than to tell the story of characters. The story of the girl’s romance seems to have distracted the writer/director Pawel Pawlikoski as me.

Some reviewers liked Pawlikowski’s direction and the cinematography. But where it drew attention, it looked clumsy and careless. Here’s the question: how do we judge film direction as “fresh” rather than careless? The short answer is: what we see is what is says.

The whole story is pictures, so the direction and cinematography have to answer, “What’s really going on?” Because the antagonist of My Summer of Love neither knows nor shows what she wants, it is impossible pass judgment on the look of the film. The unglamorous cinematography and direction look like an attempt to put the verdict in our hands, but without giving us evidence. Cinematography can’t tell us much about characters who have no subtext to reveal.

High Tension

This is a genre that thrives on the premise, “given one or more women and an isolated location, a psycho killer will – must – appear and attack.” So let’s take this one – two female college students drive to the countryside home of one of the girls to study for the weekend - as read. Enter psycho killer.

The second act, however, is full of conventions of the genre that are neatly presented and turn the plot wheels steadily. Each solid, if not eye-poppingly inventive, development created the sense of claustrophobic dread that we gladly pay ten bucks for. The clever turns throughout fall into the near-escape and weapons-in-the-hands-those-who-might-turn-against-someone category to keep you wondering “when” and “how.”

The ending? Pure tripe. A lazy trick. A cheat. But then, consider the premise.

Sunday, July 10

Batman Begins

Loved: The turning point in Bruce Wayne’s (Christian Bale) training in the Tibetan fastness of R’as Al Ghul (Ken Watanabe). This is a beautiful, simple, visual expression of the transformation of the man into Batman. Wayne remakes himself into one of the black-clad fighters dancing and drilling in the ring with Ducard (Liam Neeson). He bests Liam Neeson, signaling he has mastered his fears, and his destiny lies in harnessing the darkness, both literal and figurative. Three cheers to director Christopher Nolan for not resorting to CGI.

Loved: Nolan’s Batman suffers a driven restlessness, which never loses the threat that cruelty or vengefulness may break out. It makes him more like the kind of hero for those of us who are not independently wealthy. In Tim Burton’s Batman (1989), Bruce Wayne is a much more reflective, and sometimes dithering, verso to his threatening Batman. Bale plays him as relentless and workaholic. His potential is broader and more surprising.

Hated: Yack, yack, yack about spiritual life and embracing one’s fears. The fighting said it all. Or should have.

Lack of focus: The movie struggled to show the redemption that Batman seeks. The movie set two inward obstacles for Wayne to overcome. The first was his fear of bats, an image tied to the abandonment he experienced when he fell into the well. The second, his guilt that he caused his parents death. Wayne overcomes his fear of bats, and of his own darkness, during his initiation by Assghoul.

Back in Gotham, I lost him. Or he lost me. The fight against injustice builds to climax against the forces of decadence and destruction. Batman fights. The more he fights, the more he wins. What does he want? Justice. Good. Can I identify with him? Perhaps, in some brainy, ought-to way. From the time Wayne and Morgan Freeman finish equipping Batman, he seems invincible. Both the man and his heart seemed impervious. Because Batman never lost, even in temporary failure, and was not vulnerable even in love, his offer to give up his life to defeat Ducard/R’as Al Ghul and save Gotham came cheap. I wanted to care. I really, really wanted to care.

A suggestion: Change the scene of the boy listening to his father’s heart in the first act. Instead, the father holds the stethoscope and the boy listens to his own heart. The father a medium, showing him his humanity. In a third act scene, when Wayne recovers the burned stethoscope, it would recall not simply the absent father, but the moral import of the man, and invoke his silent admonition to live up to his humanity.

Saturday, July 9

Mr. and Mrs. Smith

This movie has fought and mostly lost the battle against celebrity gossip and to my mind, its own marketing, to find someone, anyone who'll say they really liked it. Despite the trailers you've seen, this is not the story you've already seen six times, simply tagging the bases and trotting home. By melting down two genres for a specialized new subgenre alloy, screenwriter Simon Kinberg has imagined a story that defies our expecations. I think this is why no one is cheering. Everything else is niggling, which see, below.

A short lesson in genres; screenwriters skip to the next paragraph. Romantic comedy - in which two people "meet cute," sense a connection, and then spend about 80-90 minutes confronting obstacles that keep them apart. They triumph, we're relieved, and all's right with the world. Action - a threat of great proportion can only be prevented by one man (sic.) usually under time pressure (death theats to children, world destruction) and a thousand devious obstacles stand in his way, to which he marshalls 1,001 still more clever strategems. Add a love interest.

Kinberg turns both of these genres inside out. Our lovers John (Brad Pitt) and Jane Smith (Angelina Jolie) begin the story married, bored, and in couples therapy. They believe, in fact, it's over. Without obstacles to romantic fulfillment, they've fallen headlong into an airless suburbia. When we think the marriage is over, too, they both run into trouble at work. While you and I worry about how to redeem unused vacation time, as A-list contract killers -- the kind of work you simply can't talk about at home -- these two both show up to kill Benjamin Diaz or Danz (Adam Brody). His interference ruins her set up; his appearance gives her a miss. Now the threat lands on each of them equally: kill the other killer and finish the job. The threat is not out there: "Hi, honey. I'm home."

John and Jane each get 48 hours grace from their employers to blow a fatal hole in his or her mate (time pressure). But given a sure kill opportunity, first John then, Jane falters. It's the reverse of romantic obstacles. In other words, "I can't kill you. I must still love you. Damn, I better think about that." Words to live by. The rest of the film does a fine job of reminding us in the midst of car chases and shoot outs that they're just discovering each other. Once that "killer" business is on the table, what can't you say? The Smith's rediscover passion, a Hollywood must, but also who they're married to.

After they're reconciled, they learn that the Diaz job (or Danz. It was Danz in the credits, I swear, but see imbd.com) job was a ploy by their shadowy employers to take them both out. Sleeping with the professional killer competition is strictly against company policy. As you would expect, they team up. But rather than make this pair a suddenly smooth, kickass team we're accustomed to in action movies, they keep on bickering like old marrieds while knocking out three tuned BMWs from their minivan.

I could niggle: Until the fighting starts, John and Jane seem tweaked on Botox and Prozac; either the movie loses balance between the romantic and the action, or Kinberg and director Doug Liman just took to many notes from studio executives; and, okay, there was some sexual heat between our heros, but please, nothing like the molten core of tabloid-bleated desire that would have served this movie well.

But really, if this new alloy is brittle in spots, it's still bright, shining, and welcome. This is refreshing treatment of genres that redeems it from "chick flick" on the one hand, and thirteen year old boys on the other.

Saturday, June 11

The Ballad of Jack and Rose

This Rebecca Miller movie (script and direction) is a love story, but without much love. The briefest possible plot summary: Jack Salvin (Daniel Day-Lewis) suffers from a bad heart and a smoking habit. He's an aging, independently weathy hippie -- the last surviving member of a communal experiment in peace and freedom. The only viable upshot of the commune is Rose Slavin (Camille Belle), his daughter. Jack knows he may die. Not even their obvious romance with one another will keep him alive.

This is such a cool yet intimate movie that it impressed me as a foreign film born in America. Hard headed, stylish, and controlled in its use of visual metaphor, Miller's movie still lacks two important elements. A protagonist that viewers care about, and a sense of inevitability.

Jack or Rose are the only good candidates for the movies' protagonist. You could argue that together they form a unit, a protagonist twinned. But that's facile, and their battle after all is not with death or separation. It is with each other.

From the earliest moments of the movie, we doubt Jack Slavin. Dying, sure, that's going to cost him. But his affection for Rose and his expressions of it make us suspicious that, even if his conscience is clean, he loves his daughter in ways that will mar her forever.

Jack invites his friend-with-benefits Kathleen (Katherine Keener) to bring some respectability to their home by moving in. Jack writes her a check -- an "early retirement" he calls it. She agrees to his belated, half-hearted attempt to protect his daughter from rumor and his opaque, consuming personality. Instead, Kathleen and her two sons, Thaddeus (Paul Dano) and Rodney (Ryan McDonald), bring the knowlege of good and evil to Jack and Rose's Eden. And when Jack finally must choose between Kathleen and Rose, we never doubt that he'll choose his daughter. But rather than struggle, he buys Kathleen out.

Rose, on the other hand, is as devoted, knowing, and defiant as the lover of any king. She first strikes back at Jack's "transaction" by giving up her virginity to the sullen and pasty Thaddeus. Is she a victim of his abuse? Objectively, yes. Does she suffer because of it? No. Is Rose force to see and stand against Jack's failures? No.

What are we to think of a young woman who only cares about her father? She does not make her own fate in this movie. She is all reaction and defense. Jack, for that matter, is simply following the fate he set in motion years earlier. Youth alone puts all of the choices in Rose's hands. And then there's the money. A storm foreshadows the move-in, Rose's childhood treehouse and refuge tumbles down. "A new chapter," Jack says. Rose learns nothing new from it. I though Camille Belle's Rose was beautiful, occasionally fascinating, often impassive. But it wasn't her story The Ballad was following.

Jack dies. Like the Norse kings, he is cremated on the pyre of his own battleship -- his commune outpost off the coast of Canada. Rose nearly surprises us with an act of senseless devotion (I'm holding back the movie's most suspenseful moment.) And the ending. Oh, the ending! Why did I not care about that coda?

Jack and Rose don't want anything, except to be left alone. What could we want for them? As their characters reveal themselves, they bolster and care for one another. Inappropriate and suspicious in its old-marrieds tone, yes, but not repellent. What will Jack's death do to Rose? Financially, she'll be fine. Emotionally, we don't know what she'll need, lose, or suffer. That ending doesn't give us any indication of how we might feel for Rose. She appears content, busy -- neither better nor worse for the experience.

Kathleen's older son Rodney provided a sparkling sidelight throughout the movie. In a world of mammals operating on instinct, Rodney -- self-conscious, wounded, witty -- knew what he was looking at. "I think you're tremendous," he says to Rose on parting at the dock. "Innocent people are dangerous. I don't think I've met one before." Rodney's vulnerability made him the most trustworthy character in the movie, and the most interesting to follow.

Jack must die. Rose must go on. Rodney was changed by the experience. I'd like to see Rodney's movie.