It's real, of course. "Be present in the moment." Simple yet profound. But forgettable, especially when I say it. But you drive 45 minutes to see the Dali Lama, and he chuckles about his car ride through (your city here) and he says, "Be present." It will resonate for days. You will notice, at least, that you're not present. Not in the moment. Suddenly the obvious is true of you. This is the Dali Lama Effect (DLE) in action.

Welcome to the Screenwriting Expo, where everything you taught yourself in the hothouse of your local coffee shop rises to the lips of some very good teachers, and seems truer, deeper, wiser. And you know what? It is. Because you wanted it. You really wanted it. I'm leery of the DLE but, O ye empty heavens, I'm grateful! I'll be sharing some of the things I relearned in coming posts.

The Darkness darkness follows a week of vacation and week of visiting family. Visiting home (or the home of the The One You Love) always raises the question: is there a story here? Naaah! Besides, one way or another, you're already writing that story.

Also, for those dogged few of you who followed a link to my journal site (Busman's Tour), forget it. It's all happening here. Now. Be present.

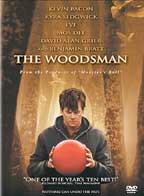

[Photo: Q: Just what kind of convention hotel did you stay in? A: The kind with "plus service" such as this.]